TL;DR

Teaching Students Writing for Online Communities

When I titled my themed first-year composition course on public digital writing "TL;DR: Writing for Online Communities," I knew I would have to explain why. If you’re not a frequent Twitter or Reddit user, you may be unfamiliar with the internet parlance of “TL;DR,” or “too long; didn’t read.” Writers themselves append the abbreviation—followed by a short summary—to the long stories they post on discussion boards or social media sites in awareness that a reader may skip to the end. The terminology demonstrates a recognition that how people write online and how they read online are sometimes at odds, especially when a writer fails to take into account the constraints of the medium and genre. Online writing is often read on a smartphone, attached to a tweet, or skimmed in a hurry. As such, those who consider online writing to be a cut-and-paste version of a traditional text miss the most effective ways to use digital genres.

(One could argue the above critique could be levied against this very course rationale, and for good reason. So, look for my own TL;DRs at the end of each section.)

Web-based writing has its own genres, affordances, and appeals to audiences. Genres are "typified rhetorical action based in recurrent situations," as defined by Carolyn R. Miller. These recurrent situations that give genres meaning can be either physical or digital as long as they provide online composers with exigences, which Miller define as "social motives" (159, 158). Over time genres develop their own conventions that are directly connected with the situation, social context, audience, and purpose to which they respond. Digital content creators do not always consider the elements of genre. Surprise: these unthinking digital content creators are often us. They are often our students.

The number of digital content creators continues to rise, as using the internet for information, communication, and self-representation is becoming increasingly common. The assumption that everyone, even in America, has access to the internet is a classist fallacy (see this recent Detroit Metro Times article about the city’s digital divide), yet most students who recently graduated from high school and are going to college tend to be comfortable with—or reliant on—the internet. A 2016 Pew Research Poll indicates at least half of those under 50 get their news from online sources. These online sources utilize online-specific conventions and genres, and they speak to specific discourse communities, which can range from fandoms—communities that bond over a particular shared interest—to echo chambers, which the Washington Post defines as "closed, non-interacting communities centered around different narratives." Their target audience affects their discourse.

Students are often part of multiple online discourse communities, though they do not always stop to consider what being an ethical, responsible, and rhetorically-savvy member of those communities requires. They have not been taught to critically examine these communities, nor their participation in them. This lack of critical examination is not just a problem for students, of course, but young adults will be shaping the future of online content through their production and/or consumption. Because of this, instructors need to go beyond evaluating online sources for academic arguments and teach students how to be participate in online spaces with careful and thoughtful boldness.

A common argument is that young adults are "digital natives," perhaps even their own sub-generation due to their comfort with technology, the implication being that they do not need to be taught how to use digital tools. While Marc Prensky's term has been critiqued for its colonial overtones (see McCutcheon for more on this critique), other researchers, like professor of educational psychology Paul Kirschner, have said even the idea of a generation able to seamlessly interact with any electronic device has no basis in science. Everyone needs to be taught to use technology thoughtfully. Familiarity does not equal thoughtful and intentional production.

The conversation about "digital natives" parallels the conversation about literacy in composition studies. For years, the field has been arguing that just because one learns to form letters in kindergarten, read words in elementary school, craft paragraphs in middle school, and write essays in high school, this does not automatically ensure that one is prepared for the level of writing and research required in college. Hence the need for college composition courses. Literacy is a continual process. The same goes for digital literacies, a term which has been much debated and frequently defined. A sample of views on digital/computer/new media literacies is included below.

(One could argue the above critique could be levied against this very course rationale, and for good reason. So, look for my own TL;DRs at the end of each section.)

Web-based writing has its own genres, affordances, and appeals to audiences. Genres are "typified rhetorical action based in recurrent situations," as defined by Carolyn R. Miller. These recurrent situations that give genres meaning can be either physical or digital as long as they provide online composers with exigences, which Miller define as "social motives" (159, 158). Over time genres develop their own conventions that are directly connected with the situation, social context, audience, and purpose to which they respond. Digital content creators do not always consider the elements of genre. Surprise: these unthinking digital content creators are often us. They are often our students.

The number of digital content creators continues to rise, as using the internet for information, communication, and self-representation is becoming increasingly common. The assumption that everyone, even in America, has access to the internet is a classist fallacy (see this recent Detroit Metro Times article about the city’s digital divide), yet most students who recently graduated from high school and are going to college tend to be comfortable with—or reliant on—the internet. A 2016 Pew Research Poll indicates at least half of those under 50 get their news from online sources. These online sources utilize online-specific conventions and genres, and they speak to specific discourse communities, which can range from fandoms—communities that bond over a particular shared interest—to echo chambers, which the Washington Post defines as "closed, non-interacting communities centered around different narratives." Their target audience affects their discourse.

Students are often part of multiple online discourse communities, though they do not always stop to consider what being an ethical, responsible, and rhetorically-savvy member of those communities requires. They have not been taught to critically examine these communities, nor their participation in them. This lack of critical examination is not just a problem for students, of course, but young adults will be shaping the future of online content through their production and/or consumption. Because of this, instructors need to go beyond evaluating online sources for academic arguments and teach students how to be participate in online spaces with careful and thoughtful boldness.

A common argument is that young adults are "digital natives," perhaps even their own sub-generation due to their comfort with technology, the implication being that they do not need to be taught how to use digital tools. While Marc Prensky's term has been critiqued for its colonial overtones (see McCutcheon for more on this critique), other researchers, like professor of educational psychology Paul Kirschner, have said even the idea of a generation able to seamlessly interact with any electronic device has no basis in science. Everyone needs to be taught to use technology thoughtfully. Familiarity does not equal thoughtful and intentional production.

The conversation about "digital natives" parallels the conversation about literacy in composition studies. For years, the field has been arguing that just because one learns to form letters in kindergarten, read words in elementary school, craft paragraphs in middle school, and write essays in high school, this does not automatically ensure that one is prepared for the level of writing and research required in college. Hence the need for college composition courses. Literacy is a continual process. The same goes for digital literacies, a term which has been much debated and frequently defined. A sample of views on digital/computer/new media literacies is included below.

Different Views on Digital Literacies

|

Digital literacy requires three competencies: "1) finding and consuming digital content; 2) creating digital content; and 3) communicating or sharing it." - Hiller Spires

|

Digital environments involve two types of reading: "offline reading," in which the text is a traditional print text read online, and "online reading," in which readers need to consider digital elements such as images and comment threads. - Donald Leu

|

|

Computer literacies involve how individuals interact with technology in three ways: functional (as users), critical (as questioners), and rhetorical (as producers). - Stuart Selber, Multiliteracies for a Digital Age

|

New media literacies involve play, performance, simulation, appropriation, multitasking, distributed cognition, collective intelligence, judgment, transmedia navigation, networking, negotiation, and visualization. - Henry Jenkins and his colleagues at Project New Media Literacies

|

While the field has not come to consensus about even the terminology related to literacy in an online environment, all of the above researchers indicate the importance of studying and promoting digital/new media literacies to impress upon students and the wider culture that effective and productive use of technologies is a learned skill, not an inherent trait based on when you were born.

Regardless of how these new literacies are characterized, educator Rueben Loewy argues that students “need to deeply, holistically, and realistically understand how the digital world works behind the scenes.” While students are engaging with (and frequently creating) online texts, they may be not be aware of how genre, audience, and purpose shape their experience of both consuming and producing those texts. By making the familiar strange and the strange familiar, classes that focus on the evaluation and production of online writing can help students start to unearth the invisible frameworks that construct texts. By focusing on online texts through an inquiry about digital spaces and identities, the themed course that I developed for a first-year composition course at Texas Christian University (to be taught in spring 2018) seeks to teach students to become effective and ethical participants in online genres and discourse communities.

Regardless of how these new literacies are characterized, educator Rueben Loewy argues that students “need to deeply, holistically, and realistically understand how the digital world works behind the scenes.” While students are engaging with (and frequently creating) online texts, they may be not be aware of how genre, audience, and purpose shape their experience of both consuming and producing those texts. By making the familiar strange and the strange familiar, classes that focus on the evaluation and production of online writing can help students start to unearth the invisible frameworks that construct texts. By focusing on online texts through an inquiry about digital spaces and identities, the themed course that I developed for a first-year composition course at Texas Christian University (to be taught in spring 2018) seeks to teach students to become effective and ethical participants in online genres and discourse communities.

TL;DR: Students frequently engage with and create online content, but they often do not consider the literacies and rhetorical choices involved in effective online writing. A course on digital writing foregrounds those considerations.

How might a class on digital writing address first-year composition learning outcomes?

This class is a themed version of ENGL 10803 Writing as Inquiry, which is the first-year composition course offered at Texas Christian University. Students must pass ENGL 10803 before taking ENGL 20803 Writing as Argument once they have reached sophomore standing.

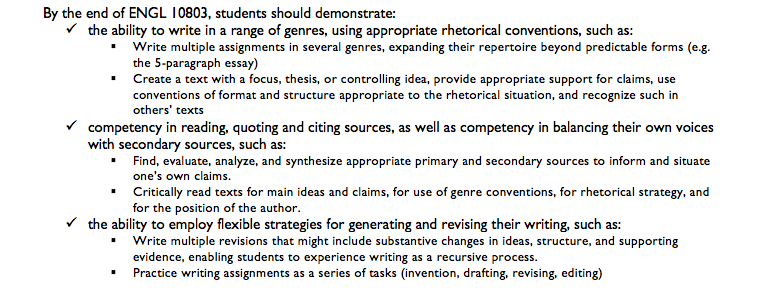

The learning outcomes for ENGL 10803 are as follows:

The learning outcomes for ENGL 10803 are as follows:

This themed course clearly meets the learning outcomes for ENGL 10803 or a similar course at another institution. As students learn about online writing, they will use and analyze a variety of genres (rhetorical analysis, blog, Wikipedia article, profile/ethnography, social media genres) and their conventions in online contexts, meeting the first ENGL 10803 outcome of writing in a range of genres beyond predictable forms. While some forms, such as social media, may raise some eyebrows, these are common genres that students are composing in and participating with, often dozens of times a day. As such, these genres are worth the academy's time and attention, in particular because students are already doing rhetorical work in those contexts but often without critical thought or conscious rhetorical strategy.

In her article "Rhetorical Choices in Facebook Discourse," Ana Amicucci found that her student made intentional decisions about her construction of self on Facebook, but she needed an opportunity to critically reflect on this persona to make clear those composing choices. Amicucchi argues that composition instructors can use students' "existing composing activity on social network sites such as Facebook to prompt awareness of and critical reflection on everyday writing practices and the transfer of rhetorical strategies from such practices to academic writing situations." She continues, "When students engage in ongoing reflection on their writing processes and the content of their writing education—including on central concepts and how students see those concepts fitting into their individual, self-defined theories of writing—they are able to see how the content of writing practice can be moved between and employed across multiple writing contexts" (48). Identifying rhetorical moves that students are already making in familiar, nonacademic contexts will help them recognize that 1) they are writers, and 2) they can make similar moves in other academic and professional genres of writing.

In terms of the other first-year writing learning outcomes, students will also learn about the rhetorical situation and online reading strategies, and use this knowledge to rhetorically analyze examples of these genres, rhetorical moves which largely address the second learning outcome. Students will learn to balance their own voices with others’ voices, particularly in the Wikipedia unit (in which they utilize traditional print and online sources) and in the profile of a community (in which they do primary research). In every unit, we will discuss how to evaluate online sources, as well as writers’ responsibilities once they become one of those online sources.

Revision of online writing is tricky, because the old version immediately disappears for the sake of a new version. Students will discuss versions, archives, and dating work, as well as how to conduct revision activities in an online environment. A key part of this course will be peer interaction both online and face-to-face, including peer review and responding to each other’s work, as students revise and re-imagine various texts for different audiences.

In her article "Rhetorical Choices in Facebook Discourse," Ana Amicucci found that her student made intentional decisions about her construction of self on Facebook, but she needed an opportunity to critically reflect on this persona to make clear those composing choices. Amicucchi argues that composition instructors can use students' "existing composing activity on social network sites such as Facebook to prompt awareness of and critical reflection on everyday writing practices and the transfer of rhetorical strategies from such practices to academic writing situations." She continues, "When students engage in ongoing reflection on their writing processes and the content of their writing education—including on central concepts and how students see those concepts fitting into their individual, self-defined theories of writing—they are able to see how the content of writing practice can be moved between and employed across multiple writing contexts" (48). Identifying rhetorical moves that students are already making in familiar, nonacademic contexts will help them recognize that 1) they are writers, and 2) they can make similar moves in other academic and professional genres of writing.

In terms of the other first-year writing learning outcomes, students will also learn about the rhetorical situation and online reading strategies, and use this knowledge to rhetorically analyze examples of these genres, rhetorical moves which largely address the second learning outcome. Students will learn to balance their own voices with others’ voices, particularly in the Wikipedia unit (in which they utilize traditional print and online sources) and in the profile of a community (in which they do primary research). In every unit, we will discuss how to evaluate online sources, as well as writers’ responsibilities once they become one of those online sources.

Revision of online writing is tricky, because the old version immediately disappears for the sake of a new version. Students will discuss versions, archives, and dating work, as well as how to conduct revision activities in an online environment. A key part of this course will be peer interaction both online and face-to-face, including peer review and responding to each other’s work, as students revise and re-imagine various texts for different audiences.

TL;DR: A course based on online public writing works toward common first-year learning outcomes, despite the context, genre, and tools being different than a traditional print-based course.

How will students' work become public? What are ethical concerns associated with students producing public work?

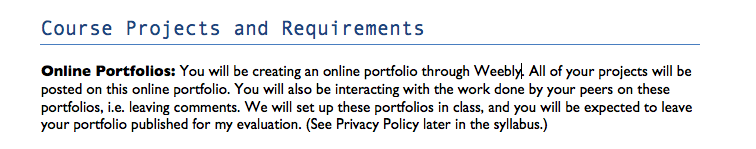

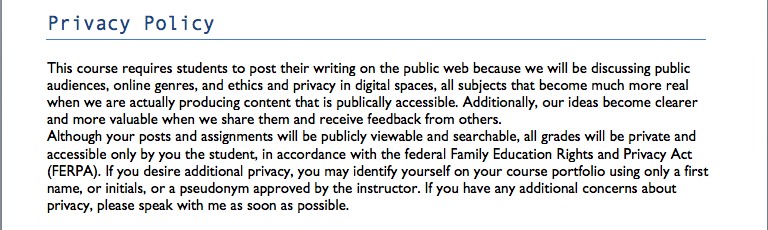

A major impetus for this course design was the idea that students will post their work online where a public audience beyond me, their instructor, may encounter it. Work will be posted on individual digital portfolios created by each student through the simple website creator, Weebly. Each of the course’s assignments– a rhetorical analysis of personal online personas, a faux-Wikipedia entry, a profile of an online community, and a remediation project – will be published on this portfolio.

There are some critiques or concerns involved in using online portfolios or blogs for a class project. For one, critics might point to the graveyard of abandoned webpages that litter the internet and note that most webpages created for classes are discarded once requirements of a class have been met. Regardless if students continue to produce content for their ENGL 10803T personal webpage or if they abandon it, they are still producing public content that may be unearthed with a specific Google search. Someone may stumble upon their work in a few days or a few months, and as such, students are responsible for the content they produce.

No longer will the teacher be the only audience for an assignment; instead, students will need to contend with the fact that their work could be read by an actual public. Students will construct their writing assignments with an ideal public audience in mind, which is a common pedagogical tactic in writing classes; the audience may include individuals who participate or have interest in the subjects and discourse communities about which the student will be writing. Students will need to navigate the ethics and responsibilities involved in being read by an actual public and make ethical decisions that reflect their purposes and goal in writing. Students will become aware that intentionality is key to online content. The class will discuss online citation, sources, and fair use in each unit, as well as issues of online privacy and ethics.

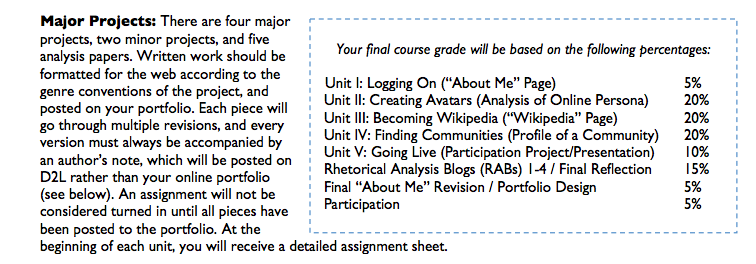

Before the class on public writing even begins, though, the instructor needs to consider issues of student privacy. Navigating the tension between public writing and student privacy is a concern brought up by associate professor of educational studies Jack Dougherty in his article "Public Writing and Student Policy." Dougherty believes writing for a public audience is important, but he also acknowledges that students deserve some degree of ownership and privacy over their own words. His conclusion is that he “may require students to post their writing in public as a course assignment (especially if [his] syllabus clearly states this in advance), but [he] may not require students to attach their names.” He also drafted a privacy policy which he appended to his syllabus; the similar statement I included in my syllabus is below.

There are some critiques or concerns involved in using online portfolios or blogs for a class project. For one, critics might point to the graveyard of abandoned webpages that litter the internet and note that most webpages created for classes are discarded once requirements of a class have been met. Regardless if students continue to produce content for their ENGL 10803T personal webpage or if they abandon it, they are still producing public content that may be unearthed with a specific Google search. Someone may stumble upon their work in a few days or a few months, and as such, students are responsible for the content they produce.

No longer will the teacher be the only audience for an assignment; instead, students will need to contend with the fact that their work could be read by an actual public. Students will construct their writing assignments with an ideal public audience in mind, which is a common pedagogical tactic in writing classes; the audience may include individuals who participate or have interest in the subjects and discourse communities about which the student will be writing. Students will need to navigate the ethics and responsibilities involved in being read by an actual public and make ethical decisions that reflect their purposes and goal in writing. Students will become aware that intentionality is key to online content. The class will discuss online citation, sources, and fair use in each unit, as well as issues of online privacy and ethics.

Before the class on public writing even begins, though, the instructor needs to consider issues of student privacy. Navigating the tension between public writing and student privacy is a concern brought up by associate professor of educational studies Jack Dougherty in his article "Public Writing and Student Policy." Dougherty believes writing for a public audience is important, but he also acknowledges that students deserve some degree of ownership and privacy over their own words. His conclusion is that he “may require students to post their writing in public as a course assignment (especially if [his] syllabus clearly states this in advance), but [he] may not require students to attach their names.” He also drafted a privacy policy which he appended to his syllabus; the similar statement I included in my syllabus is below.

While I will make clear in the early days of the course that students should not take my themed course if they are uncomfortable posting their words online, I also understand that there may be situations in which a student may want to take this course but have very real concerns about their privacy. As such, students should be able to decide how they would like to be identified on their public site, and they may take steps to conceal their identity in assignments.

My goal is to push students to encounter the idea of a real audience, a real person, reading their work. While that may be frightening to students, I also want them to realize that they are already writing for public audiences daily, particularly on social media sites. I also want them to become more comfortable taking ownership of their online identity, and one way to do that is through the creation and design of a personal online portfolio, through which a person can control and craft their digital presence for a particular audience.

My goal is to push students to encounter the idea of a real audience, a real person, reading their work. While that may be frightening to students, I also want them to realize that they are already writing for public audiences daily, particularly on social media sites. I also want them to become more comfortable taking ownership of their online identity, and one way to do that is through the creation and design of a personal online portfolio, through which a person can control and craft their digital presence for a particular audience.

TL;DR: Students will post their work on digital portfolios, and the class will use the public nature of the portfolio to frame issues of privacy, ethics, and audience. Also, protecting students' privacy must be balanced with the learning opportunity of a public audience, so an instructor must have policies in place from day one of the class.

What is the basic structure of each unit?

The major digital genres in which the students will compose are: rhetorical analysis, blog, Wikipedia page, profile, and a visual genre of their choice (remediation). Given that students will likely not have created in the online genres we will be exploring in this course, each unit is built to move the students from identifying conventions through guided analysis to individual analysis before students begin composing in the genre. Each unit will roughly follow the same pattern (though not always in this exact order):

As each unit depends on students understanding genre, conventions, and analysis, students will complete a RAB (Rhetorical Analysis Blog) for each genre. The RAB involves analyzing an example in that unit's genre; each student will find their own example, which means by the time students go to write their own assignment, they will have at least 20 models. The students will post their RABs in the blog section of their digital portfolio, and their classmates will then be required to read and comment upon each others’ RABs. The goal of this online interaction is to take the discussion out of the classroom and provide students with the opportunity to both engage with each others’ work and see additional examples of the online genres. In an attempt to discourage perfunctory responses, I will provide a different prompt each unit for RAB responses, highlighting different genre conventions and types of rhetorical analysis which students should look for in their classmates' RABs.

Additionally, each draft of a unit’s project will include an author’s memo, in which students discuss the specific rhetorical choices they made for their projects using the language we have discussed to talk about the conventions of each genre. This reflection will be especially necessary in these online genres, as students struggle with how to engage in these formats, mediums, and conventions. They may be unsuccessful in their attempt to use a new genre, and their discussion of this “failure” in their author’s note will be key to my assessment and their learning. This author's note will not be posted to their digital portfolio; instead, it will be posted in our course management system and read only by me. This author's note provides a respite from the public writing in which they can honestly discuss the process they have undertaken to compose these digital texts.

Having this basic structure for each unit will scaffold the learning of each new digital genre and provide consistency for students as they engage in online environments. Built into this structure are opportunities for public engagement with classmates that will help build community, as well as some private process writing in which students can reflect honestly about the work they have completed without the pressure of a public audience. All of these elements will aid in student understanding of online genres and conventions, as they identify, analyze, and interact in each unit.

- Introduction to the genre: discussion of purpose, audience, context, conventions

- Whole class rhetorical analysis and discussion of genre example

- Rhetorical analysis blog (RAB): students find their own examples and post analysis on their portfolios; classmates read and respond to three analyses; whole class discussion about samples/analyses

- Invention/creation

- Drafting

- Peer review

- Revision and publication

- Reflection (author's note)

As each unit depends on students understanding genre, conventions, and analysis, students will complete a RAB (Rhetorical Analysis Blog) for each genre. The RAB involves analyzing an example in that unit's genre; each student will find their own example, which means by the time students go to write their own assignment, they will have at least 20 models. The students will post their RABs in the blog section of their digital portfolio, and their classmates will then be required to read and comment upon each others’ RABs. The goal of this online interaction is to take the discussion out of the classroom and provide students with the opportunity to both engage with each others’ work and see additional examples of the online genres. In an attempt to discourage perfunctory responses, I will provide a different prompt each unit for RAB responses, highlighting different genre conventions and types of rhetorical analysis which students should look for in their classmates' RABs.

Additionally, each draft of a unit’s project will include an author’s memo, in which students discuss the specific rhetorical choices they made for their projects using the language we have discussed to talk about the conventions of each genre. This reflection will be especially necessary in these online genres, as students struggle with how to engage in these formats, mediums, and conventions. They may be unsuccessful in their attempt to use a new genre, and their discussion of this “failure” in their author’s note will be key to my assessment and their learning. This author's note will not be posted to their digital portfolio; instead, it will be posted in our course management system and read only by me. This author's note provides a respite from the public writing in which they can honestly discuss the process they have undertaken to compose these digital texts.

Having this basic structure for each unit will scaffold the learning of each new digital genre and provide consistency for students as they engage in online environments. Built into this structure are opportunities for public engagement with classmates that will help build community, as well as some private process writing in which students can reflect honestly about the work they have completed without the pressure of a public audience. All of these elements will aid in student understanding of online genres and conventions, as they identify, analyze, and interact in each unit.

TL;DR: The basic structure - modeling, analysis, interaction, and reflection - of each unit helps scaffold student learning and provides consistency for students.

What will each unit entail, and how will they build on each other?

Each unit of the course builds on the concepts of the previous unit. The students will move from personal inquiry to inquiry into a familiar community (where a student will write largely as an insider) to inquiry into an unfamiliar community (where a student will write largely as an outsider).

Unit 1: Logging On

"About Me" page

|

In this initial unit, the students will set up their online portfolios through the simple web site creator Weebly. I will introduce the concept of genre using materials from Bawarshi, Reiff, Miller, and Dethier; in our roles as both consumers and producers of digital content, we will begin to see how genres and their conventions function online. We will discuss issues of privacy and identification, and we will go over the basics of web design.

Each student will begin creating their digital portfolios, making their own rhetorical design choices. I will require that students have a standard menu and include both a blog section and an “About Me” section. I will have my own class Weebly site that will serve as both a model and a central hub for the rest of the sites. In this short introductory unit, the “About Me” section of their individual portfolios will be the central writing focus, as students decide how to define themselves as writers and individuals. |

Unit II: Creating Avatars

Profile of Online Persona

|

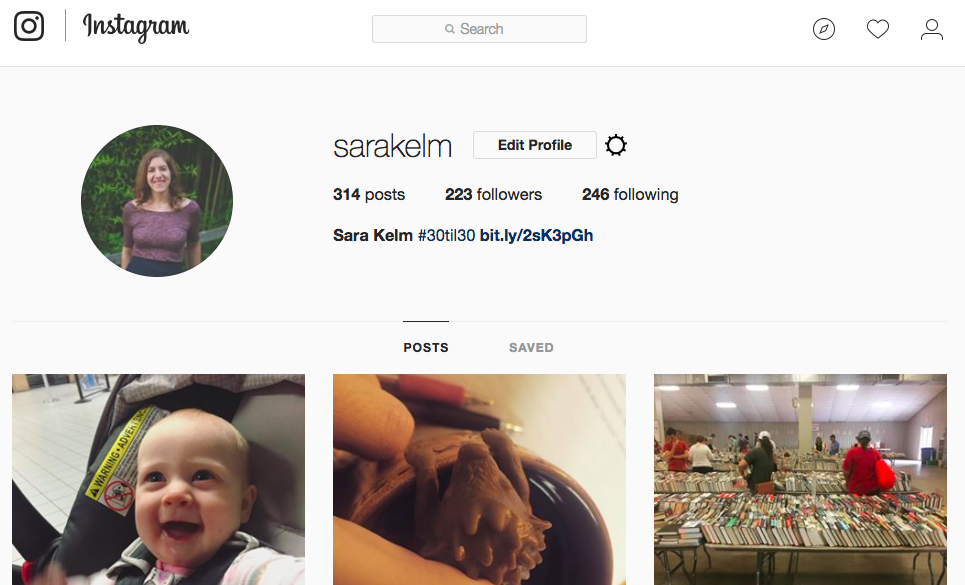

This unit combines personal inquiry with analysis, as students rhetorically analyze their own constructed online personas. We will discuss rhetorical strategies, particularly logos, ethos, and pathos, used in creating personas on a particular social media platform like Instagram or Facebook. We will also identify the different genre conventions of different social media sites, along with continuing our discussion about online security and privacy.

First, students will complete a RAB on a celebrity’s social media page. Then, students will move to their own lives, analyzing how they are presenting themselves through their social media and online presence and considering how that persona may be effective (or ineffective) for particular audiences. Primarily, students will endeavor to articulate how they make the rhetorical choices they do on a site like Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. Students will be required to provide visual proof of their findings, images from their own social media pages. In regards to privacy, student identities may still be concealed in this project if the student wishes (through blurred images and pseudonyms).If students do not use social media or have not composed an online persona, alternate projects will be arranged in conjunction with the student's own online use. As students confront the fact that their public personas are rhetorical, focusing on personal use gives issues of rhetorical effectiveness more importance than focusing on what someone else is doing. Students are saying something to various audiences through social media, whether they recognize it or not. Through this unit, students will learn to use rhetorical strategies to analyze both visual and textual components of their own making, learning about themselves as online composers and appeals to public audiences in the process. |

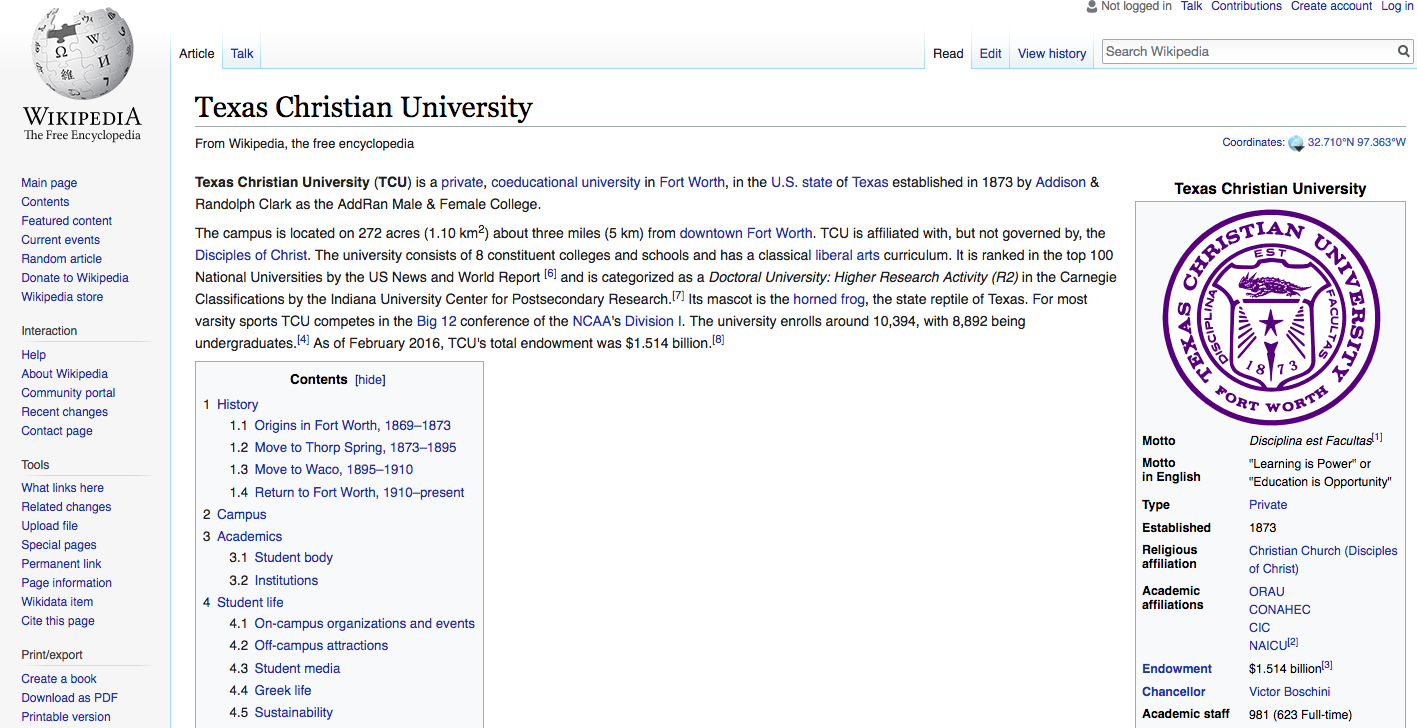

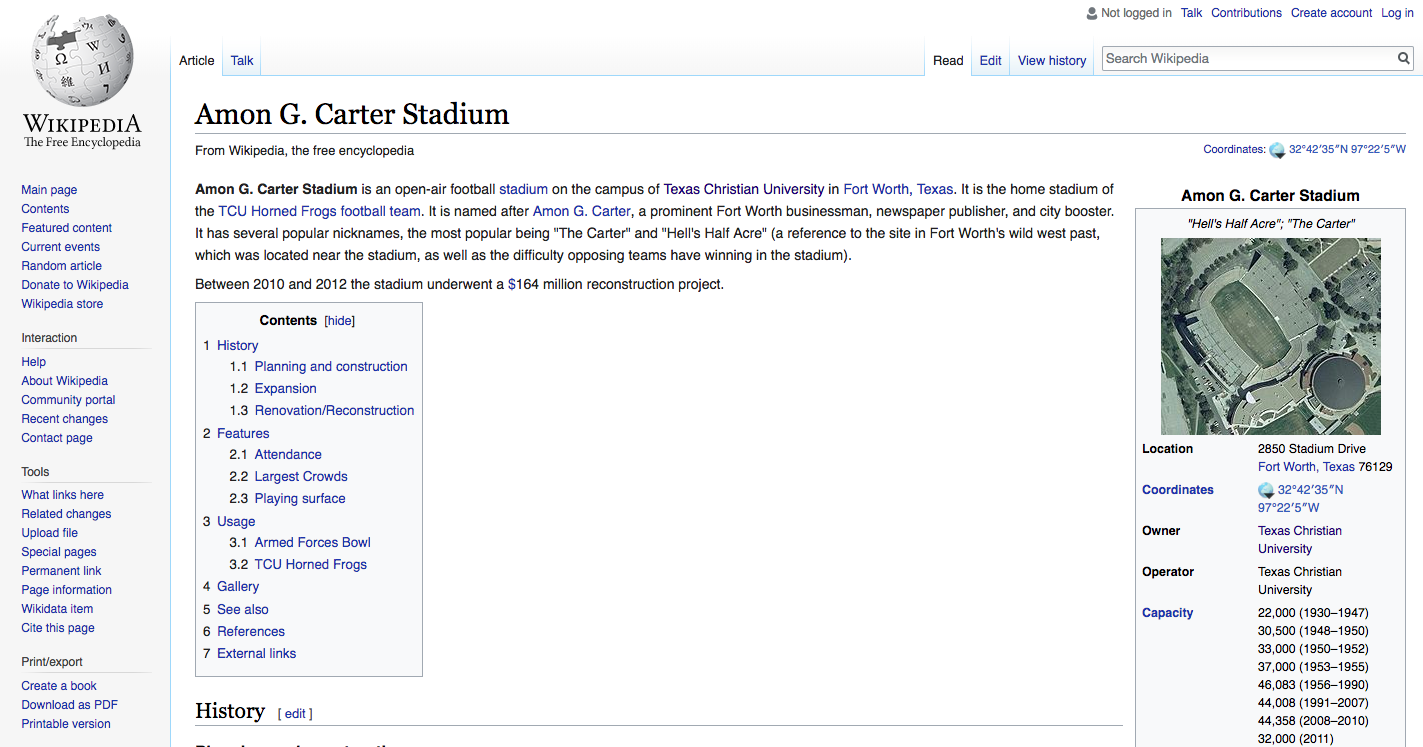

Unit III: Becoming Wikipedia

TCU "Wikipedia" Page

|

In this unit, after doing a RAB on a Wikipedia entry of their own selection, students will collaborate on faux-Wikipedia page entries about a TCU institution (a person, place, event, etc.) that does not already have a Wikipedia page. These TCU-pedia pages will be posted on their digital portfolios with hyperlinks, demonstrating the networking and interconnectedness of information on the web. Collaboration between classmates will foster a similar interconnectedness, teaching students how to write and work in teams, and how to divide up the research work, which will likely involve interviews, on-site visits, and creation of visuals.

Other instructors have had students edit or compose actual Wikipedia pages (Graham, Senier), a process which can be guided by the nonprofit organization Wiki Education. I have elected not to do this, as writing for Wikipedia through Wiki Education requires at least six weeks of class time, and in this current class format, that length of time is prohibitive. I do recognize, though, that posting student work in places other than their personal portfolios would make the idea of audience real. So at the end of the unit, we will discuss which teams' articles are the most Wikipedia-esque and why. At that point, students may revise and submit their articles to Wikipedia for publication, gaining additional points on their assignment. A large component of the unit will be evaluating Wikipedia itself as a resource for general and academic knowledge, particularly investigating who composes Wikipedia entries and how they develop their ethos. In their own compositions, students will consider the Five Pillars, which are the fundamental principles of Wikipedia, and students will need to carefully evaluate the sources they use to create their TCU-pedia page. I will ask students to hyperlink to sources and each others’ pages, creating a web of TCU information. They will also practice citation for online sources, summary, and selection of information. Visuals will be an important component of these entries, so we will consider visual rhetoric and copyright issues. Overall, students will learn valuable information about research and intellectual property that will inform both their use of Wikipedia pages and their other research and citation work outside of ENGL 10803. |

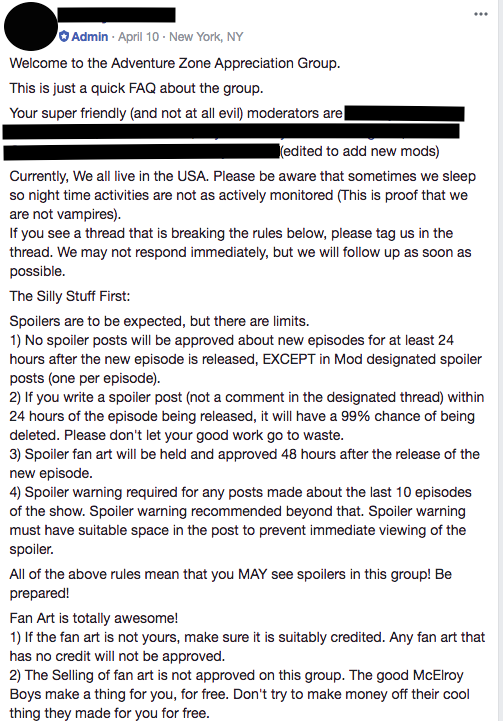

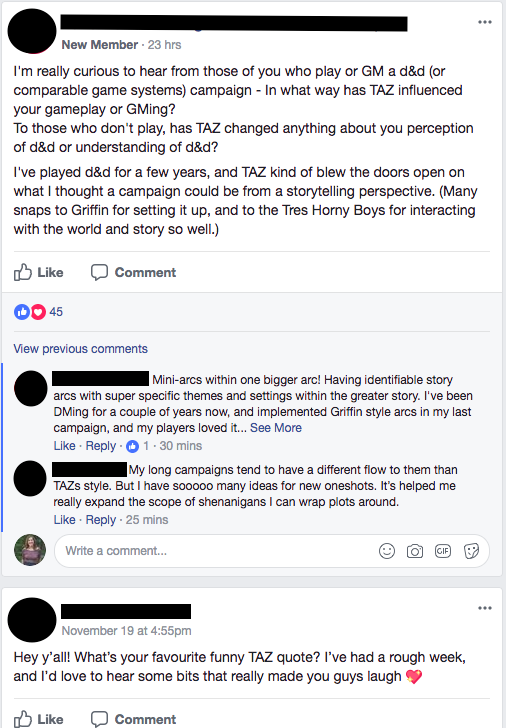

Unit IV: Finding Communities

Profile of an Online Community

|

This unit will require students to find and analyze the discourse of an online community. This assignment relates to Henry Jenkins' ideas of participatory culture. Jenkins says the internet has “the ability to transform personal reaction into social interaction, spectator culture into participatory culture,” which means students need a wider understanding of primary research, interviewing, visuals, ethical representation, ethnography, visual rhetoric, larger significance, and evidence for claims (as qtd in Urbanski 5). Participatory culture can be a framework used to look at particular online communities, whether they are advocacy groups, support pages, or fandoms. Accessibility to the internet has made it possible for unique communities to emerge, as like-minded people from all over the world are able to find each other and form groups based on shared interests. From podcast fan pages to Johnlock fan fiction communities to Facebook pages for parents with children on the autism spectrum, these communities spring up and quickly create their own ways of communicating and interacting around a shared interest.

A shared discussion between the fields of social sciences, cultural studies, gender studies, and rhetoric has been about the ethics of researching and representing communities, particularly of which the researcher is not part. In particular, feminist researchers--who are concerned with issues of power, identity, and representation--wonder how researchers can engage these communities in careful, transparent, just, dialogic, and critically reflexive ways. Heidi McKee and James Porter argue issues of ethical research become even more potent in a digital environment in their article "Rhetorica Online: Feminist Research Practices in Cyberspace." As McKee and Porter discuss, sometimes in communities, particularly ones that are "closed" to non-members (such as the Facebook group to the right), researchers can have difficulty determining what is public content and what is private content, or what is text-based research or what is person-based. When does informed consent need to be given? Should the researcher identify herself before conducting her research? How much participation in the community is ethical? In constructing this assignment, I have kept those ethical considerations in mind, and we will discuss these tensions in class. Students will first write a RAB on a profile of a community or a celebrity in order to identify different types of primary research methods and ways of integrating research. Students will look at how a journalist or researcher represents the qualities and goals of someone else. Then the students will write their own profile of an online community or fandom. As students select a community to profile, I will ask them to select either 1) a community of which they are not part but would like to join, based on shared interests, or 2) a community of which they are a part but not an active member in the discourse (i.e. a Facebook group that they do not visit or post in regularly). They will be encouraged to contact a member of the community for an interview if possible, presenting themselves as researchers and anticipating concerns that may emerge. In their profile, students will analyze the rhetoric, interaction, and compositions that typifies the group, as well as identifying their own positionality as researchers when it comes to this group (are they an insider/outsider? what is their experience with this subject and group?) and considering how that positionality affects their profile. Overall, in this unit, students will learn how to do primary research, synthesize sources, and represent someone’s words and interests with respect and thoughtfulness. |

Unit V: Going Live

Visual Remediation

|

Finally, in the last unit, students will remediate their profile of an online community and create a visual representation of the community. Students will analyze both their visual and the rhetorical choices they made in its creation for their final RAB. They will then present their findings about the online community, using their visual, to the rest of the class during the final time.

This unit allows students to practice two other ways of communicating: visually and orally. While they will not have to do additional research, they will need to consider how best to use the research they have completed to effectively address a face-to-face audience. Their visual will be posted on their portfolio, though their presentation will be a large part of their grade for this unit. Additionally in this unit, students will revise their “About Me” pages, clean up any website design, and write a final reflection to be turned in to our course management system, not posted publicly on their digital portfolio. On the final day of class, they will “turn in” their final digital portfolios that contain all of the work they have done over the course of the semester. After the portfolios are graded, students are free to do with their portfolio as they wish. |

TL;DR: Each unit builds on the previous one as students compose in different online genres and learn about the ways online writing facilitates communication and connection. They will also learn about evaluating and using sources, both primary and secondary, as well as ways to use digital genre conventions ethically and responsibly to create online content that reflects the self and others.

What readings will this course use?

For this class, I chose to assign Twenty-One Genres and How to Write Them by Brock Dethier. Somewhat unconventional for a textbook, Dethier’s book is brief, more like a mass market paperback, but the text focuses on genre and the moves made in those genres. Dethier covers conventional genres like literary analyses alongside less commonly taught genres, such as e-mails and wikis. The language of genre moves to discuss the construction of texts will enhance the language of genre conventions, which refers to what actually results from those genre moves. Also, as Dethier's book does not cover research and citation in depth, I will be supplementing the text with sections from other textbooks, such as Bruce Ballenger's The Curious Writer and Wysocki and Lynch's text on multimodal communication, Compose, Design, Advocate (my use will not exceed 10% of any supplemental textbook).

I will also assign a number of online texts, some that discuss various online issues and others that show genres in action, like this profile by Leslie Jamison about the digital community Second Life and this Wikipedia page about what Wikipedia is not. This section of the reading list will constantly be in flux, as the internet is always in flux. I will select readings that are responsive to the current climate. Additionally, students will identify their own texts for RABs, so rather than the instructor finding a variety of examples to help students learn conventions of the form, students will do this work for each other.

I will also assign a number of online texts, some that discuss various online issues and others that show genres in action, like this profile by Leslie Jamison about the digital community Second Life and this Wikipedia page about what Wikipedia is not. This section of the reading list will constantly be in flux, as the internet is always in flux. I will select readings that are responsive to the current climate. Additionally, students will identify their own texts for RABs, so rather than the instructor finding a variety of examples to help students learn conventions of the form, students will do this work for each other.

TL;DR: This online public writing class relies on a foundation of print-based text about genre, but will also utilize various online public texts that respond to the current climate and the digital genres students will produce.

How will the instructor assess student work?

One of the challenges with any multimodal or digital work (or any composition work in general) is assessment. Troy Hicks writes about the challenge in his book Assessing Students’ Digital Writing. He quotes Stephen Tchudi as making a distinction between evaluation—which implies pre-determined criteria—and assessment, which focuses more on practical concerns, i.e. how well something works. Hicks also refers to the National Writing Project’s work on multimodal writing assessment that identifies five different domains that instructors should attend to in their assessment: (1) artifact, (2) context, (3) substance, (4) process management and technique, and (5) habits of mind. Ultimately, instructors “must account for both process and product” in assessment of digital work (130). Hicks makes the following passionate point: “students are writing for a global audience, and whether we support them in that process, making it transparent and engaging in our writing classrooms, is up to us. The world judges our students on their writing, and we must take the old adage of ‘teaching the process’ much more seriously” (123).

Assessment in this course will consider both process and product, considering how the student developed a piece of online writing and how well it works for a particular public audience. Though the writing is public, assessment will not be; all assessment will be done through our course management system, not on the digital portfolio. Since drafts and process work will look differently in a digital context, I will emphasize the importance of reflection, using authors’ notes as the vehicle through which students can communicate their processes. As students are working in new genres, I am particularly interested in how they approach writing tasks and understand their role in public writing, and I will emphasize process narratives as key to students' assessment. Additionally, I will weigh the work students do commenting on each others’ blogs with the classmate interactions they have face-to-face. Both will contribute to our classroom culture, and both will impact the work our classroom does, collectively and individually. Finally, there will be a component of both self-assessment and classmate assessment.

Assessment in this course will consider both process and product, considering how the student developed a piece of online writing and how well it works for a particular public audience. Though the writing is public, assessment will not be; all assessment will be done through our course management system, not on the digital portfolio. Since drafts and process work will look differently in a digital context, I will emphasize the importance of reflection, using authors’ notes as the vehicle through which students can communicate their processes. As students are working in new genres, I am particularly interested in how they approach writing tasks and understand their role in public writing, and I will emphasize process narratives as key to students' assessment. Additionally, I will weigh the work students do commenting on each others’ blogs with the classmate interactions they have face-to-face. Both will contribute to our classroom culture, and both will impact the work our classroom does, collectively and individually. Finally, there will be a component of both self-assessment and classmate assessment.

TL;DR: Assessment will pay attention to both private process and public product, involving significant reflection and self- and peer-evaluation.

Final thoughts...

While this class may appear narrow in its approach to writing (hence, its themed nature), in fact its goals match the learning outcomes of many first-year composition classes. The difference is in its focus on writing being public and digital. Analyzing and creating public digital texts will prompt students to engage in inquiry about the online participation of themselves and others, as they ask and answer questions about the information, resources, and communities found in online contexts. I believe working with online genres is a valuable endeavor as online rhetoric becomes more prevalent and, in many contexts, more divisive. My hope is that inviting students to examine why and how online writing functions will encourage them to become more ethical and responsible consumers and producers of online content.